The Next Great Migration in America is Here

The geography of the American Midwest is mighty appealing in a world on fire.

Great Lakes from space

Photo courtesy of USEPA Environmental-Protection-Agency

In American history, “The Great Migration” refers to the mass migration of African Americans from the South to the North and West between about 1916 and 1970. It is estimated that between 5 - 7 million African Americans made this move to leave an unhospitable South for a better life in the North and West.

This migration has been somewhat reversed since 1970, as many African-American families have returned to the South, drawn by improving governance and social factors, a cheaper cost of living, better weather, and reconnecting family ties. The numbers of the Great Migration have not been reversed, but they have moved significantly. In 1900, about 90% of African Americans lived in the South. By 1970, that number had dropped to 53%. By 2020, about 57% of the country's African American population lived in the South, not a total reversal, but the reversal of a trend.

On a smaller scale, the Great Depression brought about mass migration within America. It is estimated that just under half a million people from the middle of America moved to California for work and more fertile land of California’s Central Valley during the Dust Bowl of the Great Depression.

America is changing again. Another great migration is starting. A 2020 report by ProPublica highlighted the changes we can expect to see:

Across the United States, some 162 million people — nearly 1 in 2 — will most likely experience a decline in the quality of their environment, namely more heat and less water. For 93 million of them, the changes could be particularly severe, and by 2070, our analysis suggests, if carbon emissions rise at extreme levels, at least 4 million Americans could find themselves living at the fringe, in places decidedly outside the ideal niche for human life.

A 2017 study titled Migration induced by sea-level rise could reshape the US population landscape, by Mathew Hauer estimates that up to 13 million Americans could be forced to leave submerged coastlines. That won’t happen overnight. But at some point, people will realize that a 30-year mortgage makes no sense in a place that might not exist in 30 years.

The real number of climate migrants within the United States over the remainder of the 21st century will dwarf the numbers of the Great Migration. Tens of millions of Americans will likely pick up stakes and move to a part of the country that they find more hospitable.

That part of the country is most likely the American Midwest.

From Rust Belt to Climate Haven.

The American Midwest has 20 percent of the world's freshwater and will have a climate more temperate than the rest of America as climate change brings more heat, more frequently. The Northwest and the Northeast will have more temperate climates as well, but they don’t have the water.

In addition to the water itself, the Great Lakes provide natural water filtration, flood control and natural nutrient cycling as water from Lake Superior makes it’s journey through lakes Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario before the St. Lawrence river takes that water to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Great Lakes provide drinking water for about 30 million people, 10% of the US population and 30% of the Canadian population. Over 200 billion liters of water per day for industry and farms along the banks of the Great Lakes.

Another thing that the Midwest offers those fleeing the South and Southwest is cheaper home prices – at least for now. Over the past two decades, the West Coast saw a pronounced appreciation in home prices. Every major city on the West Coast has grown by more than the national average over the past two decades. The story of the South is mixed. The boom in relocation to the South from the end of the 20th century has slowed, but the story for home prices in the South is still better than in the Midwest. In the American South, the boom has continued, just not at the rate of the West. Cities in the Midwest saw slower home price growth than the average over the past two decades. That may be about to change.

It's not all good news for the Great Lakes region.

Human activity and industry have brought pollution and development that have degraded the habitats surrounding the lakes. Industrial and agricultural pollutants now threaten some life in the lakes. As more people move to the region to escape climate change, those challenges won’t go away.

Increased evaporation from the lakes has caused lower water levels which has forced some ships to reduce their cargo so that they are not as heavy, so they don’t hit the bottom of the lake in some places. This has increased shipping costs. It is normal for the Great Lakes to go through cycles of rising and falling, but with climate change, the lows will get lower, causing more travel and shipping problems and the highs will get higher – often contributing to more intense and more damaging storms. Higher lakes can lead to more flooding and sewage damaging the drinking supply if water treatment facilities are overrun by a lake.

More evaporating water from the lakes can turbocharge storms, leading to more damaging weather events. The large cities in the Great Lakes region that sit right on the lake, such as Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo will have to increasingly adapt to more severe weather threats that will only grow more intense as temperatures rise. Storm damage from storms will likely increase until and if climate change is tackled, or until areas of these cities retreat somewhat from the lakeshore.

So why will everyone move to the Midwest?

Not everyone will move to the Midwest in the coming decades. Moving is a pain, and expensive, and involves taking kids away from their friends. A whole family has to start over in a new and often unfamiliar place. People don’t decide to move across the country lightly. But these aren’t normal times. Mass migrations have happened in the past because there was a challenge that was just too insurmountable to deal with for those who left. Climate change is that challenge.

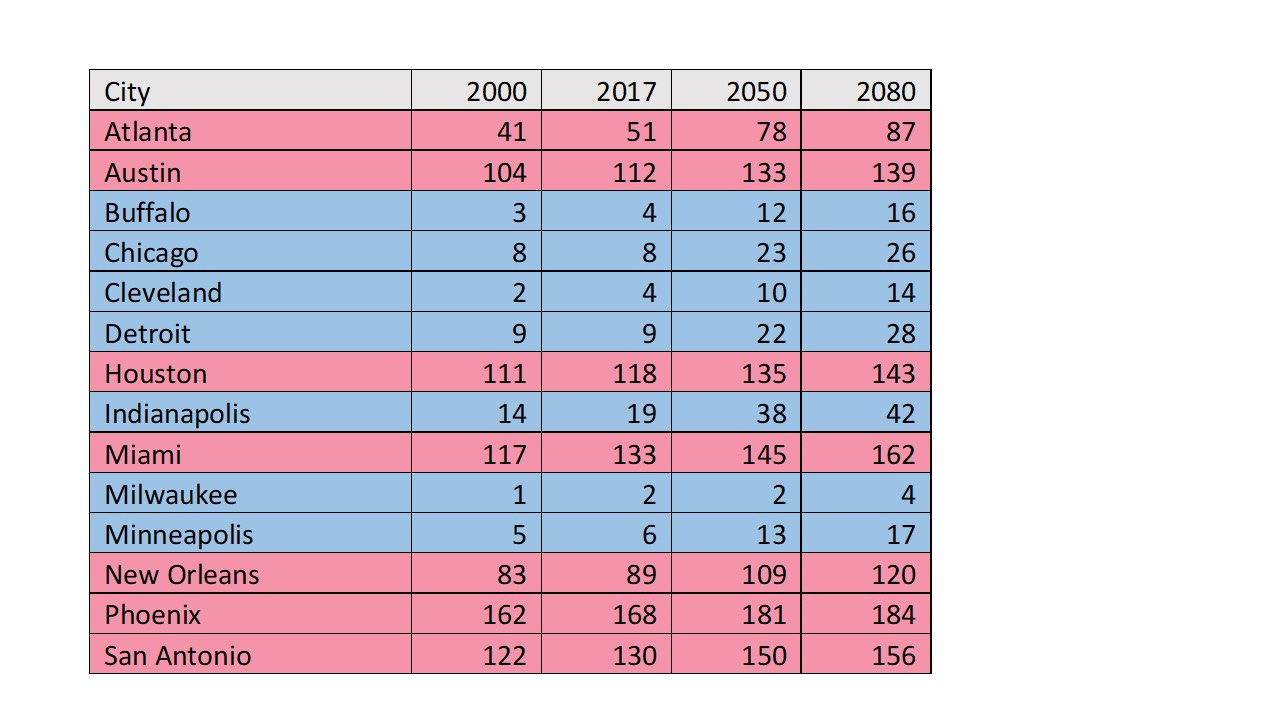

In 2018, the New York Times published a simulator that let you put in the year you were born and would let you know the number of days in that year over 90 degrees Fahrenheit, how many 90-degree days there were in the year before the study – 2017. The tool also estimated how many 90-degree days to expect in the distant future. I pulled up the website and looked at some of the largest cities in the South and the Midwest to compare what we can expect in the coming decades. I put in 2000 as the base year and let the simulator run. I cheated a little with Buffalo. It is not considered a Midwestern city, but it is far North and next to a Great Lake, so it is an apt city to include.

Each column below shows the number of days above 90 degrees Fahrenheit for that year in the past, and the expected number of above 90-degree days in the future. For 2050 and 2080, the simulator showed the expected number with a range extending both above and beyond that number. So, the numbers in the future are in the middle of a range.

Notice that Indianapolis, which is not near a Great Lake, will be a little hotter than those Midwestern Cities that are attached to a Great Lake. However, Indianapolis will be a much cooler place to be than anywhere in the South in the coming years.

In 2050, all things being equal, are people going to want to move their families to Houston, or Chicago? Phoenix or Cleveland? Miami of Buffalo?

Number of 90-degree F days per year.

In June of this year, authorities in Arizona passed rules stating that they will not grant certifications for new developments in the Phoenix area because there just isn’t enough water to support these developments.

Living in the state most susceptible to the ravages of climate change is already expensive. It is only going to get more expensive. Florida’s homeowner’s insurance rates are four times the national average. Insurance companies don’t have the luxury of telling themselves climate change isn’t a big deal. They’ve run the numbers. None of the big national homeowner insurance companies in the U.S. have much of a presence in Florida. In July of 2023, Farmers Insurance announced it would stop offering its policies in Florida including home, auto, and umbrella policies, citing increased hurricane risks. Before this announcement, Farmers Insurance covered about 100,000 Floridians.

Most homeowners in Florida now get their insurance from local insurance companies, many of which don’t have the resources of their larger national competitors to absorb what will become ever-increasing liabilities in the state because of climate change. The state offers Citizens Property Insurance Corp. as the insurer of last resort in Florida. But at some point, large swaths of the state will become uninsurable. It’s just a matter of when not if. When people can’t insure their homes anymore what will they do? Will they just choose to be uninsured and hope for the best, or will they go somewhere where they can still get insurance? Over time, the latter is more likely.

The South will lose its tax base.

Part of this equation that people don’t often think about are the dollars that come with the people who move. Yes, people may move to escape heat and severe weather. But they will also move where there is opportunity and a growing community.

A tax base on the move is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Every person that moves to Minneapolis or Indianapolis brings with them all the money they spend, and more importantly to these cities – the taxes they pay. As people move to Midwestern cities, these cities will see an influx of tax dollars that will improve infrastructure, schools, hospitals and the quality of life in that city and the region.

These tax dollars will be leaving the South and Southwest and all the things those tax dollars currently pay for – will suffer.

Midwestern cities are already starting to sell themselves as “climate havens.”

There is no such thing as a climate haven. Yes, Milwaukee, Wisconsin will have much fewer problems from extreme heat, and coastal flooding than other parts of America. But the residents of Milwaukee, or any other Midwestern town will face challenges from climate change. They will see more severe weather, just like anywhere else, they will be subject to droughts, and rivers flooding, and a stressed agriculture system that will struggle to feed the world – which of course includes Milwaukee.

But Milwaukee will be much cooler, and won’t run out of water, and those two things will matter more to Americans with each passing year.

Expect mayors of Midwestern cities to subtly and not so subtly sell their cities as places to escape the worst effects of climate change. In 2019, Buffalo, New York, Mayor Byron Brown called the city a “climate refuge.” The city of Cincinnati, Ohio, called itself a future climate refuge in its 2023 Green Cincinnati Plan. Anyone running for mayor of a big Midwestern city would be foolish to not sell their city as a climate haven in the coming years. They will say it, and people in the South and West will increasingly listen.

Real Estate Opportunity

I’m sure that I’m not the first one to think of this but buying low-priced residential real estate in the American Midwest now, while prices are low and selling it to people fleeing the South over the coming decades seems like a decent little money-making venture.

I don’t have the capital to do that myself just now, but as a former Clevelander, I could tell you a good place to start.

Give me a call.