Tipping Points

The ones we haven't passed yet ... but soon may

Tipping points and feedback loops

By 2050, global average temperatures are projected to rise significantly above pre-industrial levels, with most scenarios pointing to about 2°C increase or more depending on emissions pathways and policy actions. High emissions scenarios see temperatures about 3°C over pre-industrial levels by mid-century.

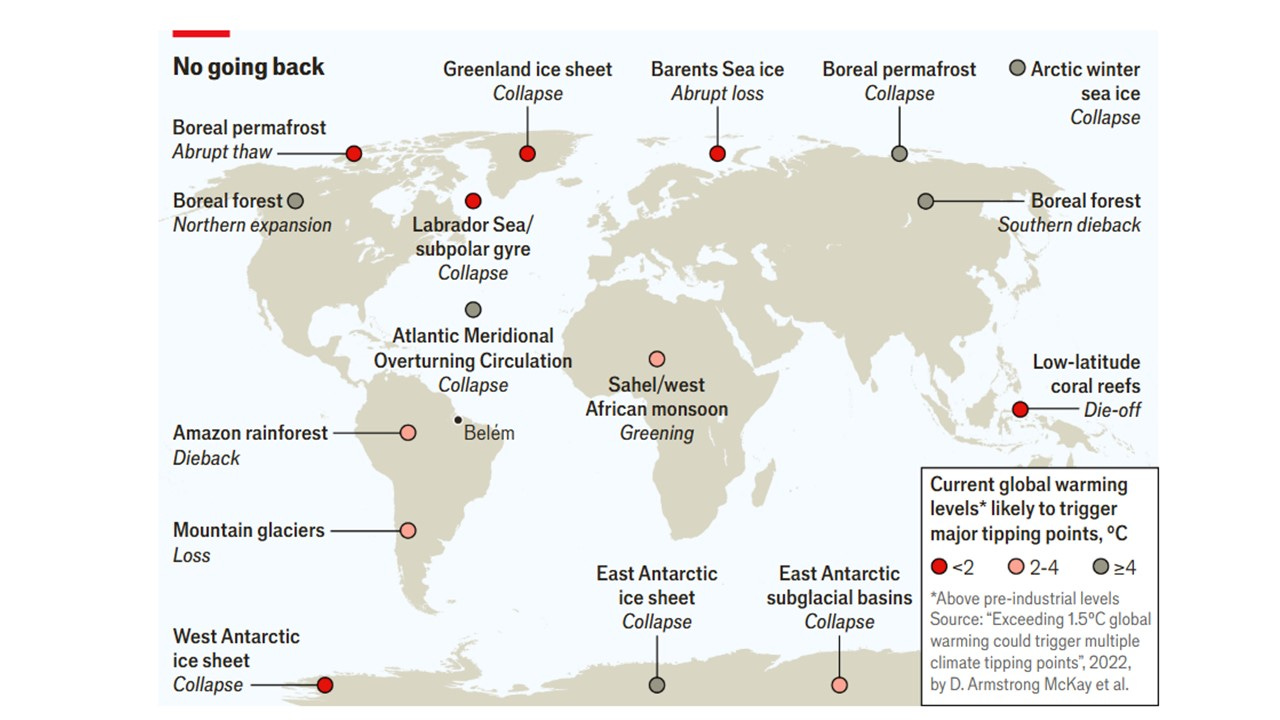

The problem of letting global warming get up to 2°C is that we may reach some bad tipping points before that. The Economist put out a story a few weeks back that had a very informative graphic, showing what tipping points may be coming and at what temperatures they might kick in.

As you can see above. There are some pretty scary tipping points right about where we are now. As of today, global average temperatures are about 1.5 above pre-industrial levels. So 2 degrees of warming isn’t far off. Let’s take a look at what to expect as the world warms, and the tipping points we will cross.

Tipping points under 2.0 degrees of warming.

A particularly scary tipping point is the melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (The WAIS). The WAIS holds enough water to raise global sea levels by about 3.3 meters (10.8 feet). This ice sheet is particularly vulnerable to ocean warming, as the land it sits on is primarily below sea level. Recent research estimates that the tipping point for irreversible loss of the WAIS is between 1.5C and 2C of global warming above industrial levels. We are quickly approaching those numbers. All of Antarctica holds enough ice to raise sea levels up to 60 meters (just under 200 feet). That’s where you get future world maps where Florida and most of the East Coast and Gulf Coast of America are gone.

Another unpleasant tipping point to consider is all the methane frozen in the land in the northern hemisphere, in the Artic, Scandinavia and Siberia, as well as areas of Patagonia, Antarctica and New Zealand in the southern hemisphere. This permafrost has stayed frozen for so long it is thought to be permanent – hence the name “permafrost”. As the climate warms, some of this permafrost is thawing. That is all kinds of not good.

The thawing of permafrost exposes carbon in the soil that microbes will then start to consume, which will release CO2 and methane. This will slowly warm the atmosphere, which will thaw the permafrost further and, well, you know the drill. The 2019 NOAA Arctic report estimates that this process is already underway and will only accelerate with more warming. The permafrost in North America is likely to give way (under 2.0 degrees of warming) than that in Siberia (under 4 degrees of warming). Great.

Tipping points between 2 - 4 degrees of warming.

The West African Monsoon (WAM) is a critical climate system that drives seasonal rainfall across the Sahel and surrounding regions. The WAM is influenced by land-sea temperature contrasts, atmospheric circulation patterns and climate change.

If warming continues, it could push the monsoon system into a new normal, either intensifying rainfall dramatically or causing prolonged droughts. The speed of global warming could cause this shift to happen suddenly, not gradually, making adaptation extremely difficult.

Reduced rainfall leads to vegetation loss, which in turn reduces moisture recycling and further weakens the monsoon. Drier conditions increase dust emissions from the Sahara, which can suppress rainfall by cooling the atmosphere and reducing cloud formation. The potential impacts are agricultural collapse in the Sahel and surrounding regions, which would lead to mass migration due to food and water insecurity, and conflict escalation over dwindling resources.

There is an amazing relationship between the Sahara Desert and the Amazon Rainforest that most people don’t know about - i didn’t until I began this research. But it shows how all of these systems are connected, and you have to consider the system as a whole when analyzing a problem. Any great change in the makeup of the Sahara, or the weather, winds, temperatures there, could have a beneficial, or devastating impact on the Amazon.

The Sahara Desert's dust is a nutrient for the Amazon Rain Forest because it contains nutrient rich phosphorus. That dust is transported across the Atlantic on the wind, and deposited in the Amazon basin. Without this annual delivery of Saharan dust, the Amazon couldn’t maintain its ecological balance. This shows just how interconnected the Earth’s systems are and how a breakdown in one place can have catastrophic impacts elsewhere.

A dieback of the Amazon Rainforest may reach a tipping point soon, where the jungle cannot grow back and becomes savanna more than a jungle. Currently, the Amazon is one big positive feedback loop. Rain in the Amazon returns to the atmosphere through evaporation, trees also return water to the atmosphere through their leaves (transpiration). This process results in a moist atmosphere and the rising upward motion of air which ultimately brings more rain.

Making the forest smaller, which we have been doing through logging and cutting away the forest to make farmland, slows down this pattern. At some point, the Amazon will become too dry to come back as a jungle on any kind of human timescale, instead turning into Savannah which would mean less evaporation and transpiration in the atmosphere, which leads to a drying of the environment, which leads to a loss of jungle, and so on. Not only does the Amazon bring rain to South America, but it is also responsible for a great deal of the oxygen we breathe. Losing that would be devastating.

Tipping points under 4 degrees of warming.

Another feedback loop is the melting of Artic Sea ice. Arctic ice, which is white, reflects sunlight back into space, thus avoiding warming. A warming planet is melting Arctic Sea ice, revealing a dark ocean underneath, which absorbs heat, thus warming the ocean, causing more melting, and so on. The melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Labrador Sea Sub Polar gyre (DOING WHAT) which may potentially happen at below 2 degrees of warming may lead to a bigger more problematic tipping point. This ocean warming can lead to a tipping point that can eventually shut down the system of currents in the Atlantic Ocean that brings warm water up to Europe. This Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) brings warm water up from the Gulf of Mexico. The cooler water from the North Atlantic and Arctic is denser than warm water, and thus sinks, which helps drive the current. As the warm waters from the Gulf of Mexico cool, they sink, releasing heat into the atmosphere, much to the delight of Europeans that would otherwise enjoy much cooler temperatures.

The Atlantic currents are part of a bigger system that acts as a conveyor belt of water that circles the world. As freshwater melts from the Artic and Greenland’s glaciers, along with increased freshwater from rain, it makes the water lighter (salt water is heavier) and less likely to sink. At some point, this could shut the AMOC down. The recent IPCC special report on 1.5C of warming concluded that it was unlikely that the AMOC would shut down anytime soon, but it has already weakened and could eventually shut down if temperature rises continue unabated. However, more recent reports warn that the AMOC could shut down much sooner, sometime between 2025 and 2095.

A shutdown of the AMOC could cool North America and Europe by about 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees C) within a decade. This would be a respite from climate change for Europe and North America but would also be a relatively permanent change to our climate, for which our society is not prepared. So, let’s not root for an AMOC shutdown as a fix for climate change. A drop by a couple degrees C would wreak havoc with North American and European agriculture, and society. Because such a scenario makes places colder, it would drive up expenses such as increased energy use as the continent adapted to a new mini-ice-age. If you are wondering, it is estimated that it would take at least 100 years, but likely much longer for the AMOC to recover.

Another tipping point you might not want to hear about is the health of phytoplankton, the tiny organisms that are at the center of the ocean food web, decreased about 40 percent from 1950 to 2010 according to a 2010 report out of Canada’s Dalhousie University. Not only does this bode ill for humanities love of seafood, but also for humanities love of breathing, as phytoplankton are thought to produce about half of the oxygen we breath. If the phytoplankton go, that may be game over man. As phytoplankton dies off there is less ocean capacity to absorb carbon because they consume CO2. This warms the ocean, killing more phytoplankton, and so on.

There are other tipping points and feedback loops out there to explore, such as, coral reef die-off, Indian monsoon shift, and boreal forest shift, but you get the picture. These huge natural systems are susceptible to collapse, which would make climate change worse based on feedback loops. Waiting around and hoping that we hold things to 2 degrees C or less isn’t a safe bet to make.

Action likely isn’t coming anytime soon, as public awareness of climate change tipping points is generally low. A 2023 study in the UK showed that less than one-third of respondents had not heard of any before the survey, and awareness levels for some individual tipping points were at best around 30-35%.

But before we get to what actions we can take, let’s have some fun using our imaginations to think about what the collapse of our societies and then perhaps our civilization would look like if we don’t get our act together. Tune in next time for that.

Thats if you believe the temperature data...

What if this graph is WRONG?

We need to question if we have any temperature increase at all!

And if we need to have any concern about climate change?

The Graph That Lied | Tom's TruthBombs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bo0YrN4Nz_c

AMOC collapse repercussions vary, but my understanding is that the likely outcome is quite a lot worse than that.