Delicious but dangerous

Photo by amirali mirhashemian on Unsplash

Humanity has a beef with beef.

In 2022, the European Commission and the United Nations released a report that estimated 34% of GHGs produced in 2015 came from food production. This echoes the findings of a similar academic study showing that in 2018 about 33% of global GHG emissions came from our food system.

The biggest driver of these emissions – by far, is beef production. An article from the Economist in late 2022, sported the provocative headline, “Treating beef like coal would make a big dent in greenhouse-gas emissions.”

They are right.

The article lays out the reasons behind beef’s large carbon footprint. Cattle emit methane, which is a powerful greenhouse gas. Cattle need large pasturelands that are often created via deforestation. This is currently a huge problem in Brazil, where large swaths of the Amazon rainforest have been cut down to make way for cattle to graze. According to the Economist, in 2010 beef was responsible for 4.3 gigatons of CO2 equivalent, while dairy cows were responsible for 1.6 gigatons. For the sake of comparison, air travel for the year 2010 was responsible for 0.85 gigatons of CO2 equivalent.

Land use is a huge driver of climate change.

Deforestation due to agricultural expansion; the conversion of forest to cropland or grassland for livestock grazing is a major cause of deforestation.

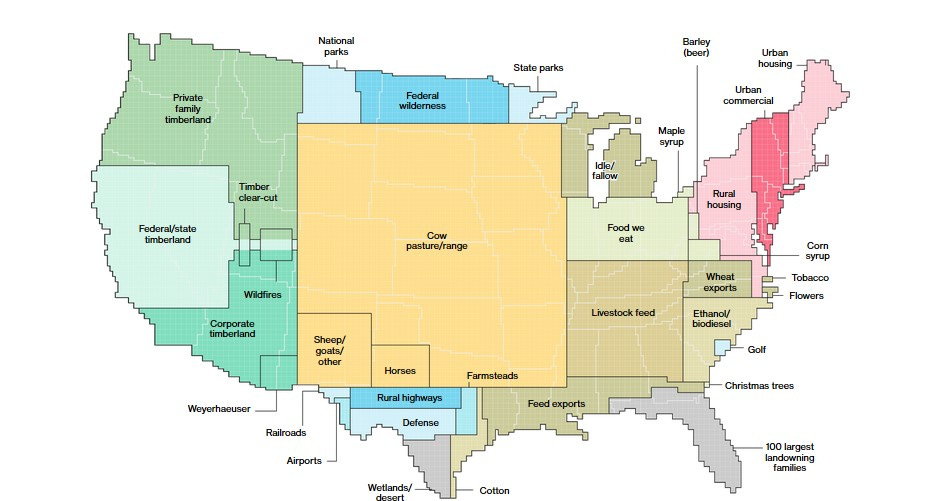

Look at the below map of land use in the United States. That big square in the middle represents just over 25 percent of the land in the lower 48 states. Over a quarter of our land is devoted to grazing, mostly for cattle. That figure doesn’t even include the feed for the cattle square just to the right of the grazing square. Add those together and over 40 percent of the land in the lower 48 states is devoted to the care of cattle.

Source: Bloomberg

I’m not here to tell you to stop eating beef or become a vegetarian. I’m not a fan of wagging my finger at people or telling them what to do. That’s not productive.

But the facts are the facts.

A diet that moves away from beef can have a huge impact on the planet. The cultivation of beef has an outsized impact on other environmental problems. Moving away from current levels of beef consumption could have profound positive effects on water conservation. Consider an article from Slate in 2021, discussing the current dire state of the drought out West and the dwindling water resources of the Colorado River.

Because of how much water is used to grow alfalfa to feed cattle to provide meat, the research suggests that if Americans stopped eating meat just one day a week, that alone would translate to a savings of water equivalent to the entire flow of the (Colorado) river. Were that ever to happen, that would solve the West’s water problems in its entirety for a long time to come.

Limiting our consumption of beef can help with most of the planetary boundaries we have crossed and some we haven’t. Climate change, biodiversity loss, land use, water use, ocean acidification, and the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles can all be positively impacted if we cut back on beef.

I went to a Catholic School as a kid. I remember that during Lent, we wouldn’t have meat on Friday. We were a very meat and potatoes family, like many in the Midwest in the US. I remember being annoyed at this. But that kid had no perspective on the impact his family’s diet had on the planet.

Now I do.

If people in the US didn’t eat beef, one day a week, we could solve the water crisis in the Colorado River and take a big dent out of climate change. That sounds like a fair deal.

I know such a development would adversely impact ranchers and others in the beef (and dairy) industries and its supply chain. To address this, we could adopt a “just transition” type package that some countries have adopted to compensate coal miners when their countries moved away from coal. Beef wouldn’t disappear, but its subsidies would likely disappear over time, and as tastes changed, much of the land reclaimed from beef production could be used in other ways to help combat climate change. Not all that land could be reforested, but just imagine if 1/7 of the land in the United States currently used for raising cattle, could be used for climate mitigation projects. This assumes Americans didn’t eat beef one day a week making 1/7 of the land dedicated to cattle now useful for climate mitigation purposes. That would have a big impact.

Again, I’m not saying you must become a vegetarian, or you are a bad person if you eat beef. I’m not a vegetarian. I was early in my life, and when I moved to New York in my late twenties, I set my vegetarianism aside so I could enjoy all the foods of the world available in New York. I don’t regret that decision. Beef tastes great, and I’m happy to enjoy Korean Barbecue, Brazilian Beef, or just a great hamburger now and again. A couple of years after I moved to New York, I went to India for a few months to work on a project. India is a largely vegetarian country, but they do eat goats, chickens, and other animals. They don’t eat cows though because they consider cows sacred. There is hardly any beef on any tables anywhere in India. I didn’t think I missed it, but when I got home, I had a craving for a burger. The best hamburger I ever had; was a simple McDonald’s Big Mac I ate once I got back to New York after three months in India. That burger tasted soooooo good.

Now, I hardly ever eat beef, because I know it’s carbon footprint and I know it isn’t the healthiest meal. I still enjoy it now and again but in moderation. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve enjoyed cooking more and discovered many great dishes to cook that are vegetarian-based, whether you use a meat substitute or not. I encourage people to try a more vegetarian diet for health and climate reasons, but I’m not going to preach to people. Just get the facts and do with them what you will.

A fact to make you think, and a new form of meat to think about.

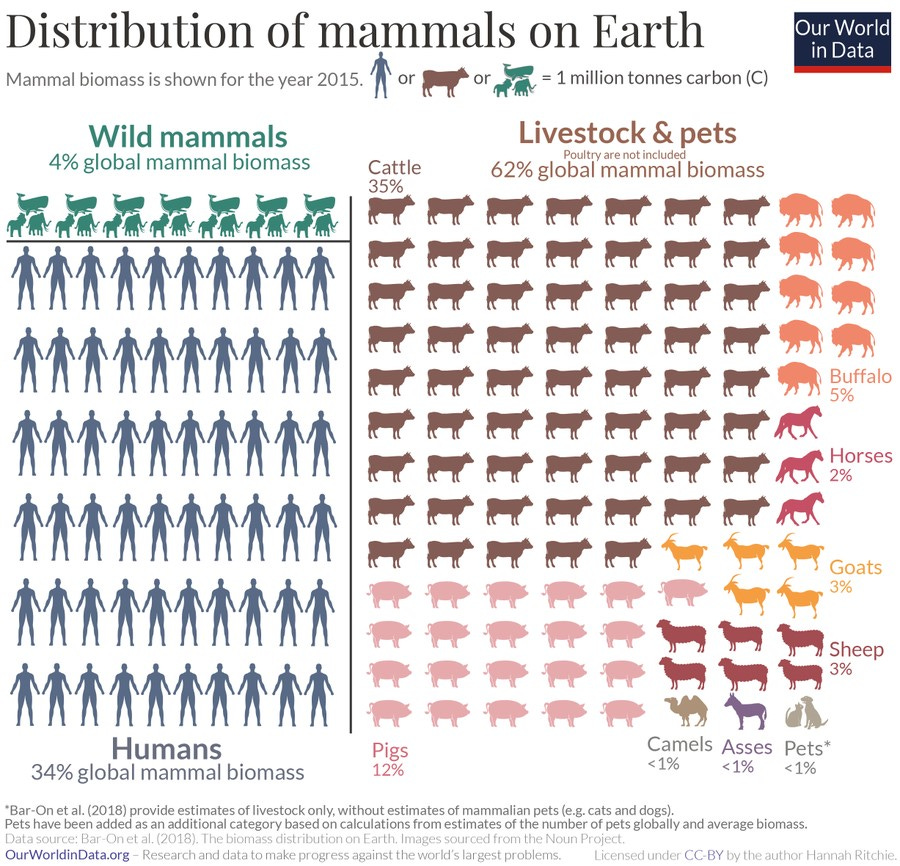

Before you move on from thinking about how our diets drive climate change, chew on this … pun intended. Livestock make up 62 percent of the world’s mammal biomass. Of all the mammals on the earth, over 60 percent of them are alive just so we can eat them. Wild mammals including huge specimens such as blue whales, orcas, elephants, and rhinos – all wild mammals - only makeup about 4 percent of the global mammal biomass. Humans account for just over one-third of the mammal biomass.

Not only are we screwing up the planet with our diets, but we are pushing wild animals further to the brink, which has severe implications for biodiversity and ecosystems. These ecosystems need predators and prey animals alike to provide services we don’t think about. Animals spread seeds as they wander their territory. Predators keep the populations of prey animals down.

Take the example of wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park to see the myriad ways that wild animals improve our habitats. When wolves were hunted out of Yellowstone, the elk population exploded because they had no real predators. This led to overgrazing and a slowdown in natural forest regrowth, as the elk would eat or trample young trees before they could mature. When wolves were added back to the park, the health of the elk herd improved as the wolves targeted weak and sick elk. The lower elk population allowed trees to grow, which provided beavers with a source of food, which resulted in more dams, and improved the health of the rivers in Yellowstone. Beavers damming rivers reduces flooding and wildlife damage, preserves fish populations, and conserves freshwater reservoirs.

Don’t worry, your hamburger will always be there.

If we cut down somewhat on our beef and dairy consumption, we may have fewer cows to look at as we drive down the highway, but the tradeoff is well worth it. Technological innovations may make those huge sprawling cow pastures obsolete, returning a not insignificant part of the American prairie to the wild, or at the very least to a carbon sink that farmers and landowners can be paid to keep fallow.

Are you ready for the lab-grown burger or steak?

Innovations in lab-grown meat may make the land-use problem obsolete. Some people won’t eat meat grown from muscle cells in a lab. When that beef becomes cheaper and when most people can’t tell the difference, they probably will. When lab-grown hamburgers debuted in the UK in 2013, the price of a hamburger from the meat was $325,000. That has already dropped to just over 11 dollars for a patty. It’s coming soon.

When the first lab-grown burgers show up at McDonald’s or Burger King, a small segment of the population will likely be furious for a couple of weeks. Then, as millions, then tens of millions, then hundreds of millions, then billions of people around the world become used to lab-grown beef, and they see their countryside rewilded, resulting in a healthier landscape for animals and humans alike – they will forget what all the fuss was about.

It won’t happen tomorrow. But the sooner it happens, and the sooner we can reclaim much of the land, the better.

Agreed. Beef is just one part of it. I'm going to be writing a few posts on food, beef was just the first. We don't need to stop eating beef. We need to eat less of it because of it's huge ecological footprint (land, water, climate, phosphorus/nitrogen), but it is just part of a bigger system.

I roll my eyes myself when someone thinks things are solved if they just don't eat beef. I'll be getting into more of that system in my coming posts. Keep the comments coming if I miss something. I appreciate your feedback, as it helps keep me and people reading this better informed.

I agree with almost all of this but there are grasslands in the west that are maintained as grasslands by the grazing of cattle. Many species of wildlife from meadow larks, badgers, weasles and hawks rely on this habitat.

Lost in this discussion is the option of sustainable grazing (rest-rotation) on appropriate lands (non-deforested) and then eating, not "grass fed" beef, but more importantly, grass FINISHED beef. Avoiding the many downsides of feedlots.