Please don’t put me back in the box.

Photo by Luke Stackpoole on Unsplash

Food system emissions were estimated at 18 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2015, or 34 percent, though down from 44 percent in 1990. That is an improvement, but that 18 billion number is still incredibly high, and likely higher today - 9 years later.

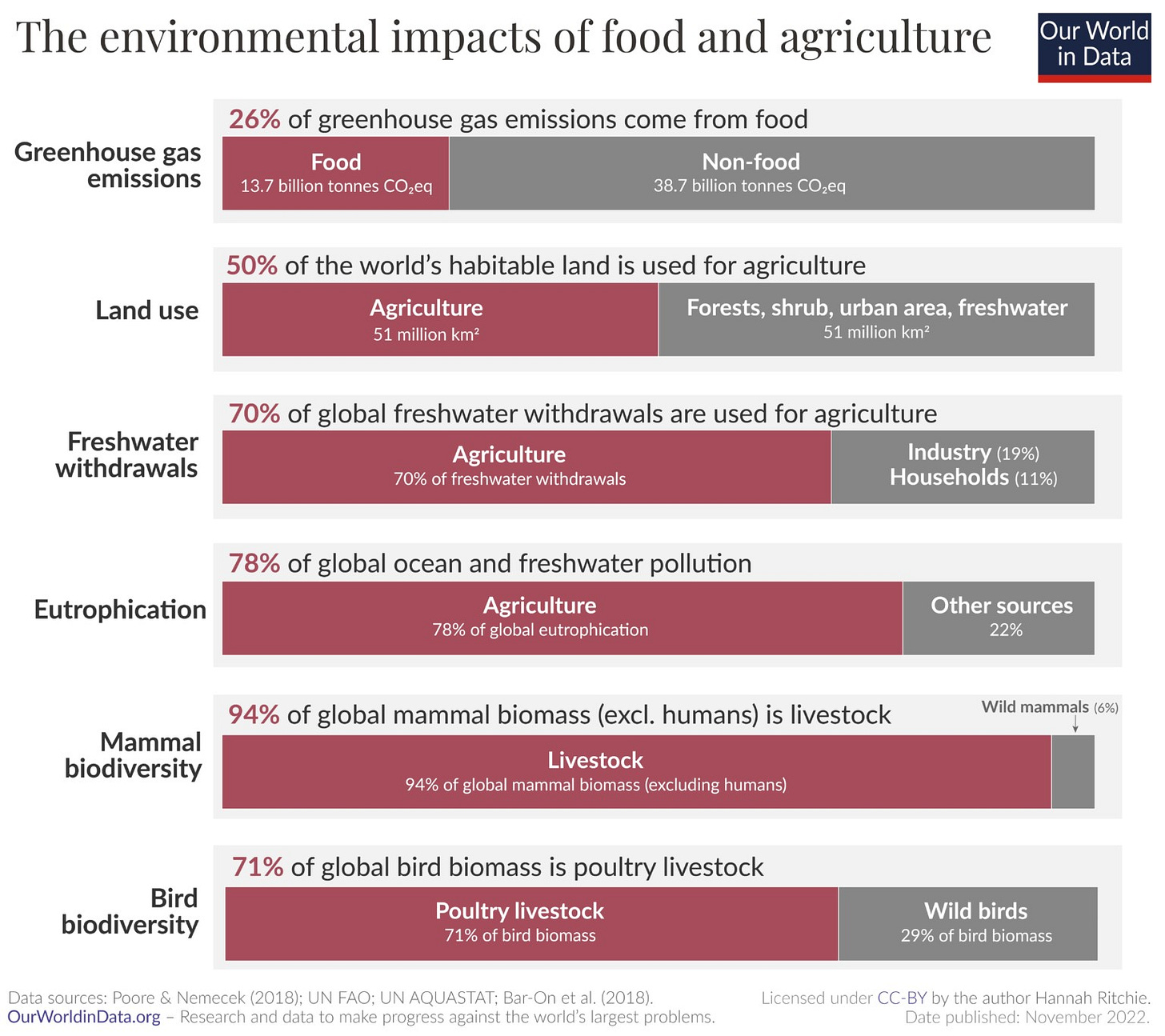

Let’s look at how our food systems impact our world. Some of these figures are stunning.

· About half of our greenhouse gases come from our food systems.

· About half of the world’s habitable land (things that aren’t deserts or ice-covered) is dedicated to

· 70% of freshwater use in the world is for agriculture

· Nearly 80% of ocean and freshwater pollution of nutrient-rich water comes from agriculture.

Pair that knowledge with this graphic about the GHG emissions of what we eat.

As a follow-up to my earlier essay on beef consumption; I was gently chastised by Dean for not differentiating between industrial agriculture, in this case, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), and more sustainable farming. I differentiated between factory farming of cattle and more sustainable methods, in my head, but not in my essay. I should have done so. Some of the lowlights of CAFOs from our friends at the Sierra Club:

- CAFOs are industrial-sized livestock operations.

- CAFO animals are confined for at least 45 days or more per year in an area without vegetation.

- CAFOs include open feedlots, as well as massive, windowless buildings where livestock are confined in boxes or stalls.

- The amount of urine and feces produced by the smallest CAFO is equivalent to the quantity of urine and feces produced by 16,000 humans.

- CAFO waste is usually not treated to reduce disease-causing pathogens, nor to remove chemicals, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, or other pollutants.

- Over 168 gases are emitted from CAFO waste, including hazardous chemicals such as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and methane.

- Airborne particulate matter is found near CAFOs and can carry disease-causing bacteria, fungus, or other pathogens.

- CAFOs may cause health effects to their neighbors from pollution damage to the air, land, and water.

Owners of CAFOs may say that the wastes produced by the livestock provide nutrients that help them offset the use of synthetic fertilizers. However, the sheer volume of wastes produced, often heavily outweighs any benefits and often overwhelms the ability of the land and crops to absorb CAFO wastes.

These factory farms exist because of demand. These CAFOs exist because demand drives economies of scale to produce the most products and the lowest price to provide the highest return for businesses and their shareholders.

Yes, we need food to live. But growing the food to feed us in a way that destroys us is a bit … insane.

We subsidies our demise in our food system as well.

A 2022 report from the environmental working group found that:

The Department of Agriculture spent almost $50 billion in subsidies for livestock operators since 1995.

By contrast, since 2018 the USDA has spent less than $30 million to support plant-based and other alternative proteins that may produce fewer greenhouse gases and may require less land than livestock.

What can you do?

As much as you can, know where your food comes from. Your fast-food burger may be harder to trace than local sources. The internet makes it easier to do this.

But the bigger impact will come from changing the system itself.

Similar to the subsidies given to oil and gas companies, we need to put food system subsidies under the microscope and phase out ones that are harmful, and increase those that are helpful. Less subsidies for factory farming, more subsidies for creating robust local food, and eliminating healthy food deserts (places where healthy foods are unavailable).

Include the “true cost” of the food system, when evaluating what we eat. This includes factoring in the environmental impact of the foods we eat and the harmful health impacts of “cheap” low-nutrition foods.

Eat the seasons. As much as possible, try to eat in season. Grapes flown in from Chile to North America are a great convenience, but it increases the price and increases the carbon footprint of those grapes in the North American winter isn’t worth it in my opinion. You can do without those grapes for a couple of months. Thousands of products have similar pollution footprints. Eating within the seasons also helps connect us to where our food comes from. If grapes are available year-round, it is easier to take them and the system that produces them – for granted.

Grow something. I am no great gardener, but I’m thankful to my parents for getting us to garden and plant trees in our yard as a kid. I am trying to do the same with our children. We likely won’t ever be self-sufficient with our food, but by connecting with the land in that way, we know better what it takes to grow our food. We appreciate it more, don’t take it for granted, and realize that we need to do more to build a better food system.

It is a political year.

This year, over half of the world will go to the polls to participate in elections. Reporters of the world, can you do us a favor? Ask those running for our highest offices when was the last time, they grew something to eat from the land or raised animals to provide for themselves and their families. Ask them how the subsidies they dole out to the food industry help the health of their constituents. It doesn’t.

In the United States, 30% of the members of the House of Representatives and 50% of the Senate have a law degree or have practiced law. How many have gotten their hands dirty – (not a metaphor)?

We need more of them to do so.

Thank you for that history Toma. I may borrow that story when explaining these issues further. It’s a good one.

Thanks James. I added clarification to that sentence so it isn't confusing.