Sacrifice Zones

As our problems mount, more of Earth’s people will be seen as disposable.

Source: Encorenature.org

A “sacrifice zone” refers to when one community’s health is sacrificed for the sake of another, often for profit or maintaining a way of life in that more fortunate community. A sacrifice zone is often a community living in proximity to pollutants, contaminated water, or some other manmade hazard. People in these communities are often poor and seen as disposable or a “cost of doing business” by those who benefit from the situation.

One clear example is Cancer Alley in the state of Louisiana, in the United States. This area of Louisiana stretches between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, has a high concentration of petrochemical plants, and as a result, boasts cancer rates 50 times higher than the national average. For those of us enjoying the plastics, chemicals, and gasoline that come from this region, we are indirectly supporting this sacrifice zone.

There are plenty of sacrifice zones around the world that we tolerate because they make our lives more convenient.

Quintero and Puchuncavi in Chile are home to the Ventanas industrial complex that includes oil refineries, petrochemical plants, coal-fired power plants, gas terminals, and a copper smelter. David Boyd, the United Nations (UN) envoy for human rights and the environment, warned that Chile is facing a “frightening and interconnected environmental crisis” that is violating the rights of millions of people at the industrial complex known as the “Chilean Chernobyl.” People from the area suffer from respiratory and cardiovascular diseases at a disproportionate rate. Infant mortality and cancer rights are also much higher than average

Kabwe, Zambia: The lead and zinc mine at Kabwe closed in 1994 after operating for nearly 100 years. The site is still negatively impacting the population. Lead poisoning has damaged the internal organs and brains of the children who live there.

There are many more sacrifice zones throughout the world where poor communities have been sacrificed to help supply the conveniences of life to the rest of the world.

Degrowth is the answer to helping minimize the number and size of these sacrifice zones. You need less mining and sacrifice zones if you consume less stuff. I hope that we get there. But the problem is likely to get worse before it gets better.

Sacrifice zones will increase to allow the energy transition.

It is estimated that the world will need about 300 new mines over the next decade to facilitate the energy transition away from our current fossil fuel-based infrastructure. A transition away from fossil fuels to electric vehicles and other greener power systems (wind, solar, etc.) will require an unheard-of ramp-up in the mining of certain metals (lithium, cobalt, and others) and rare earth minerals needed to create the solar, wind and battery resources imagined in an energy transition.

The new mining resources are likely going to be in similar places as today’s mines. They will most often be in communities with little recourse against companies or governments. We are likely looking at least dozens of new sacrifice zones popping up in the coming decades if the green energy transition ramps up at expected rates.

If this happens, we will see an exponential increase in the sacrifice of poor people on this planet, mostly in the Global South.

But wait, it gets worse.

Climate change and the other planetary boundaries we have crossed will likely expand the definition of sacrifice zones to include places where living standards will precipitously diminish due to environmental degradation not directly caused by industry or mining. In some cases, these zones will become largely unlivable and will be abandoned.

Sacrifice zones may come to encompass whole cities with familiar names.

Jakarta, Indonesia, home to about 10 million people has been called the “fastest-sinking city in the world” and is sinking about 2 to 4 inches each year due to excessive groundwater drainage. Rising sea levels will make matters worse. Things are getting so bad that the country is already moving its capital from Jakarta to the under-construction city of Nusantara, about 1,200 miles away. According to the World Economic Forum, cities such as Dhaka, Bangladesh (population 22 million); Lagos Nigeria (population 15 million) and Bangkok, Thailand (population 9 million) could also be substantially underwater by the end of the century. These megacities and others like them, won’t be sacrificed tomorrow, but at the rate we are going, they will be eventually.

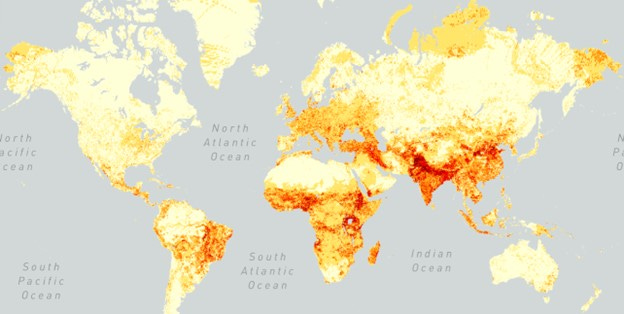

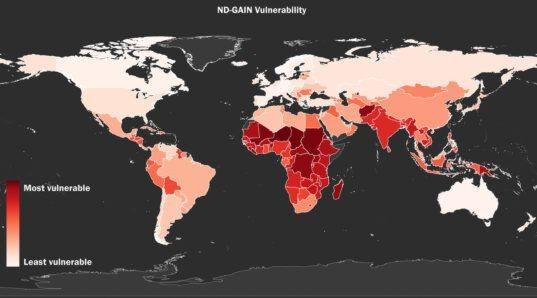

If you search for a map of countries or regions most at risk from climate change, you will come up with something similar to the map below from a Plos One study that identifies the 10 countries most at risk from climate change. This map looks like many of its kind with areas of Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia suffering the most from climate change.

Source: Plos One

If you haven’t already, you will be hearing the phrase “wet bulb temperature” a lot more in the coming years. The wet bulb temperature is the temperature above which the human body can no longer safely regulate a safe body temperature through sweating. This temperature is generally around 35 degrees Celsius, or 95 degrees Fahrenheit. The wet bulb temperature is equal to a temperature of 95 degrees Fahrenheit at 100% humidity, or 115 F at 50% humidity. The temperature you see reported on the news is the “dry bulb temperature”.

Once the temperature goes over 35 degrees C, we rely on sweating to keep us cool. The “wet bulb temperature” includes the chilling impact of evaporation, so it is normally lower than the “dry bulb temperature.” But once the wet-bulb temperature goes about 35 degrees C, not even sweating can lower your body temperature. At that point, your body will begin to overheat, and if you don’t get out of that situation, you are in a world of trouble, as your organs will start shutting down. Expect your local weather person to start reporting more on wet bulb temperatures in the coming years.

As I write this in 2024, there are few places on earth where the wet bulb temperature routinely spikes above 35 degrees C. But with each passing year, that list will grow, and the temperature will stay above this dangerous point for longer periods. Places that are now just on the happy side of the “safe” zone in summer, will become more and more unbearable to live in. Some of these places, especially in Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia will lose tens if not hundreds of millions of people, mostly through migration, but plenty of millions through heat-related deaths. There are parts of India, Afghanistan, and Pakistan where there is no air conditioning and no electricity. Many people in these places now live just below the wet bulb temperature through the worst parts of the summer. That temperature will be breached more and more consistently. Millions of people will die due to the heat, and tens of millions more will leave because life is just not possible there anymore.

These places risk becoming sacrifice zones because of heat. If in the future there are months out of the year that people can’t live in these places, people won’t live in these places at all.

Sacrifice zones can be a good thing.

Sacrifice zones may end up being a good idea in some situations. This would be a case where nature is allowed to regenerate and human development is abandoned. There are plenty of barrier islands and coastlines around the world that were once mangroves and swamps. If we strategically retreat from some of these areas and let the mangroves and swamps return, it could slow down sea level rise and blunt the impact of severe storms and coastal flooding. We could also rewild and reforest places that have been cleared for cattle or human development to restore forests or other wild places.

A strategic retreat from certain places – sacrificing them to allow nature to heal and restore – may just be the best decision. A little humility about our role in nature, and an admission that we cannot dominate it, would be the best decision in the long run.

Thanks Geoffrey. Keep up the good work yourself.

Excellent!